|

There’s nothing quite like international travel all by your lonesome. Though it was strange to do at first, I came to really enjoy it. You can obviously do this in your home country, but there’s something special about being in a foreign land, left to your own devices, and doing your best to live like the locals even though you don’t know much of the language or many of the customs. To be fair, this can lead to some bad surprises. When I was solo in Romania one time, I purchased what I thought to be a lovely pot of yoghurt for breakfast. When I opened it up the next morning, I made the horrifying discovery that it was actually sour cream. Not the taste sensation I had planned to start my day with. However, sometimes solo travel leads to good surprises, even if they are very stressful and don’t feel good at the time. This was the case on my first trip to the Kozel Brewery in Velké Popovice, Czech Republic. Having been a fan of Kozel beer since our first visit to Prague, we always planned to visit the brewery. However, due to some scheduling snafus, only one of us could actually make it there. I knew from Czech friends that this was a popular tour, so I booked my ticket well in advance. I was even able to get onto an English tour, as my Czech is wildly insufficient for understanding the nuances of brewing beer. Unfortunately for me, traffic was horrible that day, and I only got there a few minutes before the start of the tour. I literally speed-walked to the gift-shop, walking past a very cute goat in the process. It was PACKED, with people buying t-shirts, coasters, and other Kozel-themed merchandise and chatting animatedly in Czech, Slovak, German, and several other languages. Looking at the time, I had about a minute to use the restroom before the tour would be called, so I chanced it. As I came back to the hall, I saw a line of people wearing brewery vests going outside. My keen eyes detected backpacks and baseball caps as well, and my amazing powers of deduction led me to conclude that brewery staff were probably unlikely to be wearing high-heeled shoes to work. “Oh my god!” I thought, “I’m missing the tour!”. I raced after them and approached the petite older woman who appeared to be in charge. I started out good, “Dobre den” (Good day – a typical polite Czech introduction) and then quickly went off the rails, “Uh… English tour?” and pointed animatedly at the ground. She seemed annoyed (rightfully so) and made it very clear that I needed to also be wearing one of these vests or I couldn’t go on the tour. So, I raced back inside, found the box of vests, and caught up with the crew. Feeling as if I’d already made a bad and very stereotypically American first impression, I sulked toward the back of the group and tried to be invisible. After some introductory remarks that I couldn’t follow, we went into a room that looked like a very fun bar, with multiple beer taps, dozens of Kozel beer mugs, and a lot of anticipatory excitement. From what I could piece together, the man behind the bar was one of the master brewers at Kozel. He was going to show the different types of beer pours that are popular in Czechia. He demonstrated four types and, indeed, he knew what he was doing. There was a pour that was British style, with no foam, called Čochtan. Then there was one that was almost entirely foam called Mlíko. In between these extremes were the Hladinka (20% - 25% foam ) and Šnyt (½ foam and ½ beer) pours. I was trying to take mental notes of the relative angles of the mug and the tap. All the while, I must say that I had a vague feeling that something was wrong. I couldn’t quite place it. It was sort of like the experience of watching any of the first three Star War films (i.e., Episodes 1-3). Something was very wrong from the get-go of each, but it was difficult to figure out why until a little time passed and that stupid Jar Jar Binks made his appearance. Then, something very unexpected happened. The bartended called up a member of the group to learn the first Czech pour. That was very surprising. Having been on several Czech beer tours, I had never seen this level of audience participation. That’s when I finally made sense of that strange, uncanny feeling… They were all speaking Czech! I was on the wrong bloody tour! My mind raced to the land of horror and catastrophe. Jesus, am I going to get kicked off the tour? Is getting on the wrong beer tour a capital offense in Czechia? They take their beer seriously here… Will they still let me pet the goats if I offer to pay the full fee? Though I’d seen this tour online, there were no English versions available when I would be at Velké Popovice, so I opted for a “standard tour” that did not involve learning to pour Kozel beer. I noticed one of my fellow tourists spoke German to a friend. I discreetly asked him auf Deutsch what the tour start time was. Yep, I was on the wrong fucking tour. Oh, the barrage of Czech obscenities I imagined would be coming from my tour guide. Then, to make matters worse, the bartender pointed at me and called me over to the tap. This was a dilemma… If I went up there I would be drawing attention to myself and my non-Czech language skills, but by saying no, I would also be drawing attention to myself. I decided to go with option number one and nervously learned how to do the Mlíko pour. I sort of cocked it up, getting a bit too much beer on the bottom, but it was a passable pour (or at least that’s what he indicated to me, probably out of Slavic pity). Then, the tour guide lady comes over and asks for my name. “This is it!” I thought catastrophically. I whispered my name to her. Instead of checking for it against her list, finding a discrepancy, and then getting cross with me, she instead pulled out a blank certificate, wrote my name on it, and lets me know that it will be provided at the end of the tour. “I just might make it through this damn tour without incident after all”… I start to relax a bit. After the pouring and drinking was done, we go outside again to see the three famous Kozel goats. I might have petted a couple of them through the cage, but one was aloof. So, what did I learn from this? First, Always check that you’re on the right tour. Second, I look stupid in a brewery vest. Perhaps most importantly, though, this experience reminded me that sometimes anxiety and stress experienced in the moment can quickly evaporate, leaving one with good memories and a snazzy certificate proving to the world that I am indeed a master Czech beer pourer. Tasting Notes

We’re most familiar with the two types of Kozel most likely to be sold outside of Czechia. These are the light lager (Ležák) and the dark lager (Černý). My personal favorite is the Ležák. It is a very refreshing, perfectly balanced beer. They use three different malts, and it is pleasantly sweet, like a really good loaf of French bread, and almost has a subtle vanilla pudding quality at the end. However, it is well hopped and nicely bitter as well (i.e., not too bitter and nowhere near an American IPA). They use the beloved Czech Premiant hops in an elegantly restrained manner. This is not fruity (or sulphury, for that matter). It is a solid, clean, tasty workhorse (workgoat?) of a beer. The Kozel Černý is the favorite choice of the other half of the PD team. The Černý is a dark beer, but you shouldn’t expect a stout flavor. It has some very nicely caramelized malts – four, to be exact – and mild hops that combine to form a very nice and rich beer with character. Not as refreshing as the Ležák, it’s more of a fall sipper than a summer chugger. The folks at Kozel even recommend serving it with some powdered cinnamon on top of the foam, preferably using one of their goat stencils (free templates can be found on their website). Though we were initially aghast at this very American-sounding idea, we tried it. We can verify that it isn’t a bad addition for a holiday beer vibe. It certainly beats most pumpkin-spiced beers we find in the US in terms of fall cheer. Where to find it outside of Czechia It is super easy to buy Kozel beer in the UK and the rest of Europe. We’ve found it carried in a number of grocery stores and even convenience stores/gas stations. Just look for bottles of Pilsner Urquell and scan around there for the cheeky goat graphic. It’s also possible, but significantly more difficult, to purchase Kozel in the US. To be honest, we’ve only found it in European grocery stores, and it’s always a pleasant surprise when we do. One of the few reliable sources we’ve found is at the Taste of Europe grocery store in Gaithersburg, Maryland. So, if you’re ever in the Washington DC area, you can give it a shot. To book your own tour at Kozel: www.velkopopovickykozel.com/#brewery-tours

0 Comments

Some of us plan and seek experiences, especially when travelling. On occasion, though, something new appears, and it is hard to not say, “sure, why not?” Thus was the case of discovering our favorite bottom-shelf Czech beer. It was an unexpectedly scorching early fall day in Prague. We had spent the previous five hours wandering the city in search of the elusive, vegetarian doctors’ sausage (post to come) and loaves of freshly boiled Knedlíky for our dinner (yes, another easter egg…). Needless to say, It was hot, we were out of water, and we were looking forward to cooling off in our hotel room for a few hours before exploring Old City Prague’s famous absinthe bars. As we approached the building, we were confronted with a minefield of Central European construction equipment. Not a good sign. Crowed around a large hole in the sidewalk were a half dozen, shirtless men in bright yellow vests that seemed strategically parted to display their Slavic pectoral muscles to the beautiful Slavic women. We tried not to judge them too harshly, and they were working hard, but this had been a quiet, pec-less location when we left, and we were on the borderline of cranky. Upon entry to the building, we noted hastily scribbled signs on computer paper that read “no water, water line break” in Czech, English, and German. This wasn’t good, either. Refreshing showers and refills of our water bottles were apparently not in our near future. We shared a knowing yet furtive glance indicating that this might not be our most relaxing of evenings as we passed the reception desk and hit the stairs. About a third of the way down the hallway toward our AC-less room, a table partially blocked our path. The table was filled, in a ramshackeled, but nonetheless compelling fashion, with aluminum cans displaying pictures of a cute goat (Kozel) and one loan water bottle. A checky note perched atop stated, “Save Water and Drink Beer”. This not only brightened our mood, but gave us a visual window into this strange Czech culture. Not to get too nerdy, but according to the World Beer Index the Czechs drink the most beer of any country in the world. 2021 records show that each Czech drinks, on average, 184 liters of beer per year. That is about 48 U.S. gallons (!!!) or enough beer to almost fill a standard wine barrel (i.e., 60 gallons). This isn’t just because beer is on average cheaper than water - to be fair, non-touristy sites serve very good beer for around 1 USD. Rather, beer production, and, by extension, drinking, has been a popular activity of Bohemia for almost 2000 years. Modern historians mostly agree that beer making in Bohemia dates to at least the 1st century C.E., if not earlier. It likely predates Slavic tribe migration. Archeological records suggest hops have been grown and traded in the region since 900 C.E. and were possibly cultivated by early Celtic tribes. Hops were of such great value during this period that (the Good) King Wenceslas had anyone caught exporting plant cuttings put to death. If you try the beer this seems somewhat less of an unreasonable punishment... During the Middle Ages beer was brewed in towns by a licensed council member or at monasteries by specially appointed clergy. Common lore suggests that beer was more popular than water at this time (duh), but there is good literature evidence to suggest that water was still a primary beverage of choice for the poor and/or the hyper religious. This is because water was free, and most spring-well sources had low to no biological pollution. Beer was expensive (as licensed commodities are) and predominately consumed by laborers and the upper echelons of society due to its high nutritional content. There are several examples of Bohemian laborers being paid their daily wages in beer rations at their local brewery. One wonders if they noticed that raises led to decreased productivity in their workers. The idea that beer was a safe drink during the Middle Ages has some merit though. Correctly prepared beer contains low amounts of bad bacteria. It is also moderately rich in carbohydrates, fat, protein, fiber, vitamins, and minerals, contains electrolytes, and boasts other “medicinal” attributes. This is not a crazy idea, as barley is now known to contain antioxidants that may boost the immune system and may reduce the risk of contracting viral infections like colds and flus. Other constituents of the frothy beverage have been identified to lower levels of inflammation. Beer was thus considered a “health food” at the time. It was sort of like Medieval spirulina. These benefits made the brewing of beer in Bohemia a lucrative endeavor until at least The Thirty Years’ War in the early 1600’s. This population and architecturally devastating timeframe decimated the Bohemian beer industry, turning beer into a pricy commodity. Beer became so highly valued at this time that it is rumored (not yet confirmed) to be used as a method of payment to Swedish forces to prevent the invasion and destruction of Kutná Hora; a storybook town that is home to Sedlec Abbey and its astounding Ossuary chapel. Flash forwards several centuries, and in the 1900’s the price of beer again dropped due to Communist-state production takeovers and subsequent state-enforced price fixing. The low, low prices made beer drinking a popular and legal recreation among Czech men. However, this also resulted in low quality brews due to a lack of government reinvestment in local agriculture technology and brewing equipment. Although price controls ended after the Velvet Revolution in 1991, the famed České Budějovice brewery Budějovický Budvar (aka, the real Budweiser) is still controlled and operated by the Czech government. We can personally attest that the modern beer brewed at Budějovice is very good! Today, the price of Czech beer is still comparatively low, but the quality has much improved. This is in part due to the revitalization of traditional Czech brewing traditions that were almost lost during the times of Communism. Czech famed Pilsners can be found in any tap room along side many other styles. When purchasing beer, it is important to note that most are labeled with the “degree scale” that represents the strength of the draft, with strength being related to the post-fermentation weight percentage of sucrose. It is not ABV (as we were initially shocked to see so many people seemingly downing 10% horsepower beer). Generally, the lower the degree scale the lower the beer's alcoholic volume. Confusingly, this scale is often accompanied by the terms lehké (light, <8 degrees), ležák (lager, 11 to 12.99 degrees), and výčepní (draught 8 to 10 degrees)... and several others. History aside, Czech beers are best drunk near or just below room temperature as the heat helps bring out their many aromatic compounds. Oh, and foam is good… very, very good. Although the beer on the stairway table wasn’t as cold as it should have been, it was free and a welcomed distraction from the heat of that fall day in Prague. Since we knew we were on “the honor system”, we only took two each to our room. As this was our first taste of lower priced Czech beer, we weren’t sure what to expect, but imagined that it would be “ok”. However, we were very much surprised by their quality and balance. Buying equivalently good beer in the states would set us back at least $8 per pint. So, we made some careful mental notes for which beers we wanted to try from a tap (i.e., both – duh) and also wanted to do a blind taste test of the other commercial brews. However, the one beer we tried that day stood horns and hooves above the others. This will be the topic of our next post.

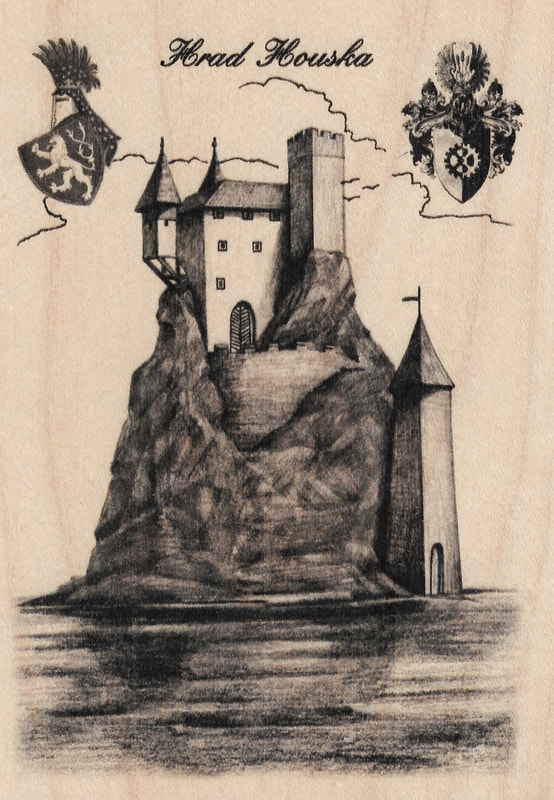

- Is the path to hell paved with refreshing Czech pilsner?? - Czechia (i.e., what Czechs call the Czech Republic) is one of our top three favorite countries to visit. It’s an even better destination when you don’t have work to do there, but it is great regardless. If you fancy castles, amazing beer, dumplings, and strange tourist sites, Czechia is difficult to beat. There are so many great castles (hrady) dotted around the country, but one, Houska, is undeniably unique. In many ways Hrad Houska doesn’t make any sense. For instance, most castles are built over a consistent source of water. After all, how terrible would it be to suffer a siege on your castle and have nothing to brew tasty pilsner beer with? Yet, Houska has no source of water except for cisterns to collect rain. Odd… Hrad Houska also lacks a kitchen. So where would a hungry soldier bake bread to enjoy his refreshing pilsner with? Strange… Further, most people building a castle would probably want the defensive side of their walls to face outward. This generally helps if you want to repel invaders. However, Hrad Houska’s defensive walls face inwards. Perplexing… All of this seems odd or even illogical until you add the missing premise… it was clearly built to cover up the gateway to hell. Yes, dear readers, a bottomless pit of eldritch danger lurks a mere hour’s drive north of Prague, and under the location of the present-day castle. Oh, the legends that surround this place. The tales speak of half-human, half-animal creatures that would emerge at night from the accursed pit and lay waste to any people unfortunate enough to cross their paths. This situation clearly had to change. It’s bad enough when a megachurch or Applebee’s moves into your neighborhood, let alone a fiery pit to hell. There’s only so much a real estate market can take before property values decline. The locals still speak of how prisoners were used to build the fortress. Builders apparently conscripted one poor convict to be lowered by rope into the accursed chasm. Upon hearing his plaintive screams, they pulled him back up only to find him aged thirty years in as many seconds. His hair turned whiter than Anderson Cooper’s and his skin looked as if he was any elderly Hollywood celebrity in the midst of a month-long Botox shortage. It was terrifying to witness. Even after the castle’s construction, the dark rumors persisted. It was even occupied by Nazis until 1945. We may never know what evil experiments, medical, occult, or otherwise, took place within its cold stone walls. Now, how much of these fun legends are true? Well, to be fair, there are some alternate histories out there. Some are backed up with historical and archaeological data that describe other motives for the castle’s construction (why do scholars always take the fun out of things… ?). However, we prefer to live in a world where Hrad Houska is our last line of defense from the many horrors of hell. Even better (i.e., a PD film script idea), we hope that, nearby, there lives a secret sect of plucky Czech warrior-poets who risk their lives every day to protect us from the ever-present scourge of demonic half-man beasts. Hopefully there will be no intensification of evil energy or an unexpected earthquake which breaks the castle’s ancient foundations. If so, things could get scary, and we may just see what these Czech warrior poets are willing to sacrifice to save the world. If we can get Christian Bale on board, we might just have a go picture here. Think of the special effects… Getting There Hrad Houska is located about an hour’s drive north of Prague and PRG airport. Anyone – even children, who were particularly tasty to the half-man beasts – can now visit the castle and get a guided tour. Keep in mind that it is closed between November and March. If you travel there in bad weather, please make sure your car has good tires as you will be on some potentially slippery roads. There are ways to get to the castle using public transportation from the airport, but it would take approximately four hours each way and you would still need to walk almost 3 kilometers from your last stop. Thus, we recommend renting a car or taking a very expensive Uber ride instead. You can also bring dogs to the castle with you, and we’re sure they’d enjoy it, but there is a modest fee for canine accompaniment. Once you’re there, the gateway to hell can be found below the chapel, more specifically where the alter now stands. The art adorning the walls is also worth a close look, as you will find depictions of armed soldiers and man-beasts scattered throughout. Side Trip

Throw a rock in Czech Republic and you’ll hit beer that is better made, and tastier, than 99% of mass produced American beer. Thus, on your way back to Prague, you might consider driving a bit further south to the charming village of Velké Popovice. There, you will find the Kozel Brewery. They also have a great brewing tour (we’ll cover it on the blog at some point). Look for the big goat and you won’t miss it. Just make sure to book the brewery tour ahead of time, especially in the summer. There are English tours, too. Link: https://hradhouska.cz/ Conclusions: This is a very fun day trip from Prague. Whether you like architecture or just enjoying strange sites, we think it’s definitely worth a visit. A Slavic friend once joked that these candy bars “taste like communism”. English information is difficult to come by for Sójový, bars in general, but some brands like Zora – maker of Sójový Řezy – have been in continuous production since the 1950s. Thus, they have survived not only communism, but the cold war and the many horrors of disco. Non-Czechs may be puzzled by this longevity when they first open the wrapper, though. That is because these tiny treats look like small cylindrical slices of very firm playdough. In the Sójový Řezy bar you will find no colorful layers of ganache, nougat, or caramel - and certainly no peanuts – but will only gaze upon a uniform off-white color that leans toward an unhealthy, somewhat jaundiced, flesh tone. Both the firmness and the color likely result from the main ingredients: sugar and ground soybean flour. Ubiquitous in many bars as a filler, soy takes center stage in these treats. But what do they taste like? Tasting Notes You will first notice the texture of these bars. They are quite chewy and firm. Not quite gritty, it is clear that pressure was used to form these little soy joys into cylinders. You will then notice that they are not sickeningly sweet like many US and UK confections, but pleasantly sugary and mild. Next, you will taste something seemingly unexpected for a Central European candy: tropical flavors! Though not overpowering, coconut is very much the dominant tone. Hints of artificial rum seem present as well. We should note, however, that there are other versions of sójový bars we may review later which use other flavorings (e.g., vanilla, chocolate). Coconut is the original, and from our humble perspective, the best. We love these things. From a traveler’s perspective, they are brilliant. They are compact and resilient, too. Easy to carry in a rucksack or your pocket, they will not get crushed like many other snack bars. We’ve all had that feeling of profound disappointment when a chocolate melts or a wafer candy disintegrates into powder. This will never be an issue with the beloved Sójový bar.

As they are made of soybean flour, they also have a good bit of protein (13 grams x 100 gram bar). So, if you fancy a snack half-way between candy and a protein bar, your dreamboat has docked. We should also mention that we buy loads of these when in Czechia, and sometimes forget about them. Interestingly, they seem to stay fresh and flavorful way past the “use by date” listed on the package, but doing that is obviously up to your own discretion. |

Categories

All

Archives

October 2025

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed